Firehose #194: ⚖️ Operating leverage. ⚖️

Why product and services marketplaces earn profits differently at scale.

One Big Thought

I’ve been spending time lately thinking about how operating leverage functions differently in product- vs. services-oriented marketplaces.

Operating leverage measures the degree to which a company can increase its profits by growing revenue. Companies segment their costs into both variable and fixed costs. The former grow proportionally with revenue, while the latter do not — at least in the short term. The split between variable and fixed costs in a business determines its ability to achieve operating leverage.

For example, consider a SaaS company that puts fixed R&D dollars into a new version of its product. Whether it ships that product to 10 or 1,000 current users, the marginal cost of doing so is small relative to the up-front investment in R&D. While the company certainly needs to spend some amount of R&D to maintain its code base, a big chunk of that initial R&D should be considered fixed costs. The SaaS company therefore has strong operating leverage on its R&D spend.

To the contrary, consider a consulting firm with hundreds of employees billing their clients on an hourly basis. If the firm wants to onboard 1 or 100 new clients, it must hire a proportional number of new consultants. It can make those consultants marginally more efficient by standardizing Powerpoint templates, or building an internal knowledge base; but, the cost of these new consultants is almost entirely variable, and therefore the firm has low operating leverage in its core service.

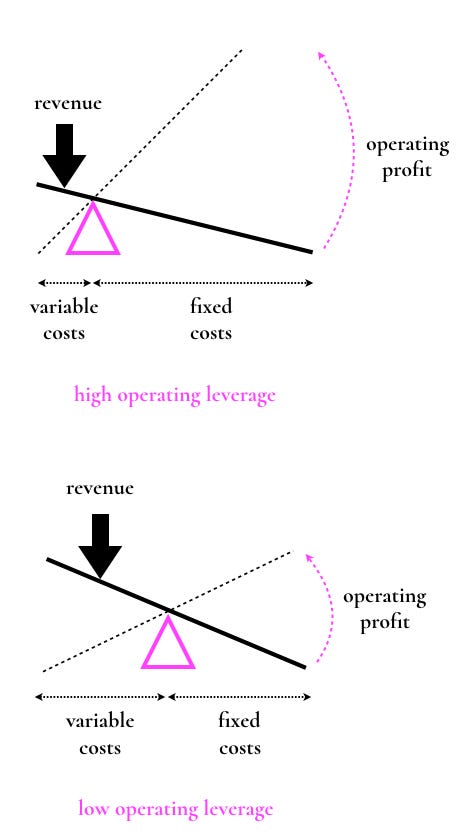

Why does operating leverage matter? Because high leverage businesses show faster operating profit growth per dollar of additional revenue. Operating leverage is akin to the mechanical advantage you get from a physical lever. In a high leverage business, you push down with a little more revenue and you get a lot of profit on the other side:

Operating leverage can be applied to various line items on the P&L. Typically most of the costs included in COGS are variable (although not always), and most of the costs “below the line” in OpEx are fixed (although, again, not always). In the simplified case that all COGS are variable and all OpEx are fixed, then gross profit margin is a good proxy for operating leverage. Software businesses, which have high leverage, also have high gross profit margins, and the opposite is true for consulting businesses.

Where this gets interesting is in complex “low margin” businesses like marketplaces. By definition, the vast majority of marketplace GMV goes to participants in the marketplace. What is left behind is there to cover the remaining variable and fixed costs. These marketplaces can generate operating leverage from several different sources, with a significant difference between product- and services-oriented marketplaces.

Product-oriented marketplaces (e.g. EBAY, TDUP*, Faire*) primarily match supply and demand in goods and then enable the payment for and fulfillment of those goods. The way these marketplaces achieve leverage is by driving the cost of the transaction down. For example, TDUP lists a line item in its OpEx called “operations, product, and technology,” as shown below from the company’s S-1 filing:

This cost line has declined from 52% of revenue in 2018 to 50% in 2019. It went back up in 2020 to 54%, but that’s likely related to COVID complicating operations. Importantly, TDUP also breaks out its non-GAAP contribution profit per order, which increased from 23% of revenue in 2018 to 36% in 2019 (and back down to 27% in 2020, again likely due to COVID impact). In addition to payment processing costs, contribution profit per order deducts so-called “distribution center operating expenses” from gross profit:

“[Distribution center operating expenses] includes inbound shipping, inbound labor, distribution center fixed costs and management labor [emphasis added], excluding stock based compensation expense, which are included within our operations, product and technology expenses.”

We can see the overall calculation here:

So, contribution profit per order breaks out fixed costs of running distribution centers. As TDUP scales more volume in its distribution centers, contribution profit should go up disproportionately. Moreover, its inbound labor costs benefit from fixed investments in automation. While those investments are likely treated as CapEx, and are therefore not included in the contribution profit calculation, the benefits of those investments should improve the inbound labor costs included in contribution profit:

We believe that average contribution profit per order, when taken collectively with our GAAP results, including gross profit per order, may be helpful to investors in understanding our order economics. We believe that if we are successful in scaling and automating our platform pursuant to our strategy, our results will show (i) an increasing average contribution profit per order over time and (ii) a growth rate in average contribution profit per order that exceeds the growth rate of average gross profit per order due to our ability to reduce inbound processing costs [emphasis added]. Such results would likely mean that our average order economics are becoming increasingly attractive and that our investments in technology and automation in our distribution centers are having a positive impact on our average order economics.

So, this line item is crucial to understanding operating leverage at TDUP. The company believes that contribution growth should outpace gross profit growth because the former includes the benefits of operating leverage, which is exactly what the “lever” analogy would imply. Indeed, the former grew 83% from 2018 to 2019, vs. 44% over the same period for the latter.

The nature of operating leverage in a business like TDUP is that it comes from a lower cost structure. Investing in automation, for example, should enable inbound processing labor to be more efficient and therefore amortize more volume over the fixed cost of distribution center employees. TDUP can then choose whether to allow those gains in profitability to flow to the bottom line, or to reinvest them, for example, in better payouts for sellers, or lower unit prices for buyers. Regardless, the source of the leverage comes from lowering the unit cost at the contribution level.

Services-oriented marketplaces (e.g. FVRR, UPWK) primarily match supply and demand in services provided by humans. Because humans in a given field and market require a certain pay rate, less flexibility exists with respect to lowering the cost of a transaction (other than typical geo-based labor arbitrage). Instead, these marketplaces put an emphasis on high quality matches and lower cognitive overhead of running a search process for labor.

For example, in its F-1 filing, FVRR discusses its innovative approach to productizing the “Gig”:

At the foundation of our platform lies an expansive catalog with over 200 categories of productized service listings, which we coined as Gigs. Each Gig has a clearly defined scope, duration and price, along with buyer-generated reviews. Using either our search or navigation tools, buyers can easily find and purchase productized services, such as logo design, video creation and editing, website development and blog writing, with prices ranging from $5 to thousands of dollars. We call this the Service-as-a-Product ("SaaP") model. Our approach fundamentally transforms the traditional freelancer staffing model into an e-commerce-like experience. Since inception, we have facilitated over 50 million transactions between over 5.5 million buyers and more than 830,000 sellers on our platform.

Still, FVRR’s take rate in these transactions has remained around 25% for several years. Its gross margins are some of the highest of any marketplace, at over 80% today. The main way in which FVRR achieves operating leverage is not by lowering costs, but by increasing the spend per customer meaningfully over time. At the time of its IPO, FVRR had more than doubled that figure over a 6 year period:

Increasing spend per buyer essentially provides operating leverage against a fixed marketing expense. The shape of the curve means that older cohorts contribute more and more to FVRR’s overall quarterly revenue, without significant additional marketing support. The below demonstrates this methodology on a cohorted basis:

One other method to increase operating leverage in a services marketplace is to invest in labor differentiation and education. I’m not aware of a public company that does this yet, but expect to see more in the coming years.** Services marketplaces will eventually provide education and additional resources to help their workers “level up” to higher pay rates — perhaps in exchange for some sort of temporal exclusivity. The trade school of the future, in fact, may not be a school at all. It could be a labor marketplace with embedded education. Because the marketplace in question earns a fixed % take rate of billings, the incentives of all parties would be aligned.

In summary, operating leverage works differently for product- vs. services-oriented marketplaces:

A product-oriented marketplace should focus on driving more volume to cover fixed costs at scale, lowering overall unit costs.

A services-oriented marketplace should focus on both driving spend per customer up in a given customer cohort and investing in supply differentiation and capabilities.

Some overlap exists in these methodologies, but firms will get the most “bang for their buck” by prioritizing the top source of operating leverage in their respective categories.

Thanks to Lenny Rachitsky for reading a draft of this post.

** If you hear of any good examples, please let me know!

Tweet of the Week

Enjoyed this newsletter?

Getting Drinking from the Firehose in your inbox via Substack is easy. Click below to subscribe:

Have some thoughts? Leave me a comment:

Or share this post on social media to get the word out:

Disclaimer: * indicates a Lightspeed portfolio company, or other company in which I have economic interest. I also have economic interest in AAPL, ABNB, ADBE, ADSK, AMT, AMZN, BABA, BRK, BLK, CCI, COUP, CRM, CRWD, GOOG/GOOGL, FB, HD, LMT, MA, MCD, MELI, MSFT, NFLX, NSRGY, NEE, NET, NFLX, NOW, NVDA, PINS, PYPL, SE, SHOP, SNAP, SPOT, SQ, TMO, TWLO, VEEV, and V.

Good article. I know is from 2021, but can I translate part of this article into Spanish with links to you and a description of your newsletter?

i like the mechanical leverage visual but it doesn't seem to compute for me... i think the revenue arrow is fucking shit up b/c revenue needs to be larger than both fixed + variable... but it's placement in your system... doesn't make sense.

but, i get it. maybe.