Firehose #190: 🎸 Creator equity. 🎸

How Web3 aligns fans and creators to take down online aggregators.

One Big Thought

A popular position in this newsletter is that small businesses are underinvested in relative to the critical role they play in the economy. Two weeks ago, I argued that the opportunity in SMB tech was hiding in plain sight, like mobile and cloud were a decade ago. At Lightspeed, our investments in Faire*, OYO*, and others have shown us that aggregating existing, offline small businesses can deliver massive efficiencies to the entire ecosystem. This is one of the reasons I’ve predicted a next-gen wave of B2B marketplaces in the coming decade.

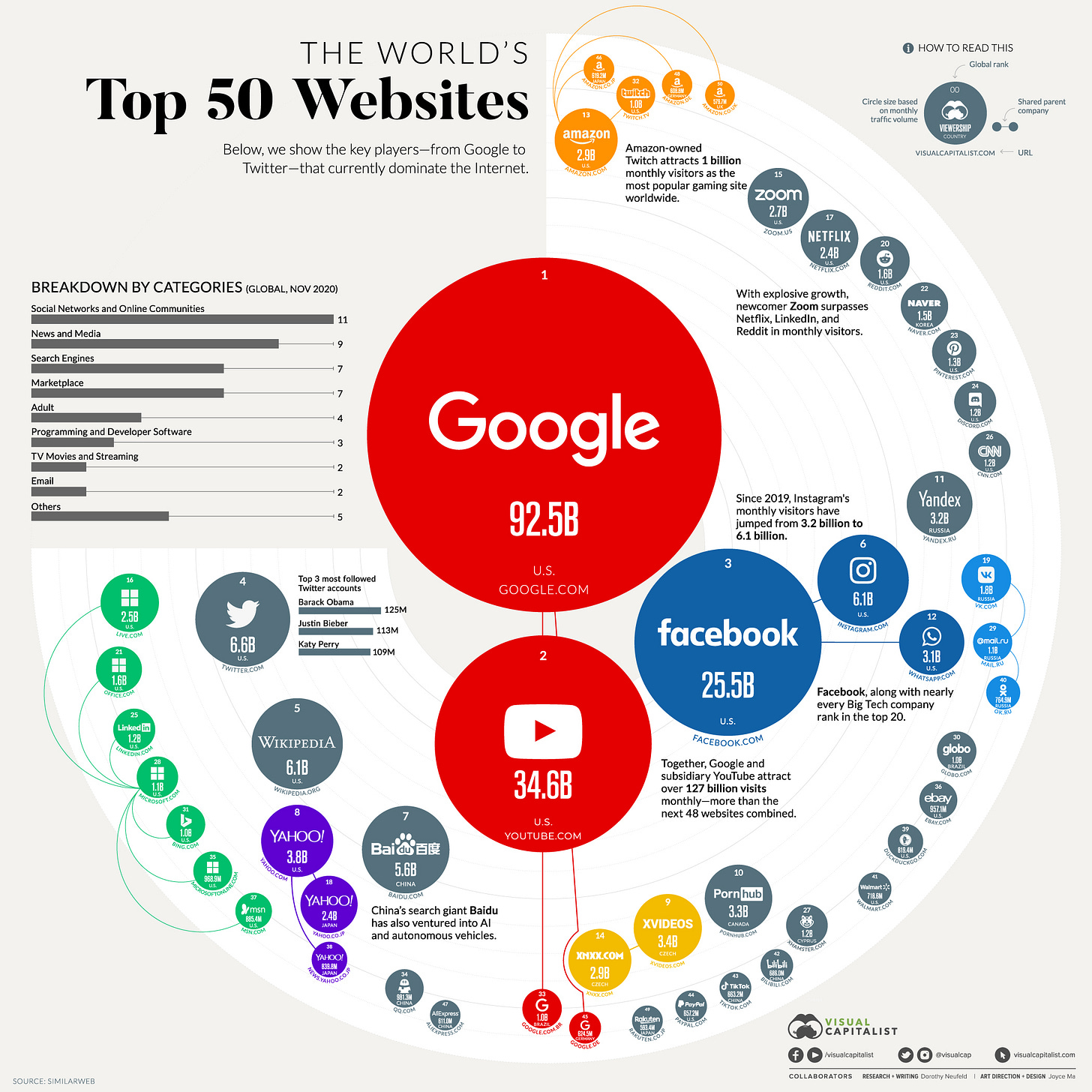

In aggregate, small, offline businesses have inherent defensibility because people live in the real world. That might sound like a trivial statement, but our offline behavior is markedly different from our online behavior. The former is taking a stroll down Main St, popping your head into various shops along the way. The latter is hanging out on only a few, very popular websites or mobile apps. Case in point: we all start our searches on Google*, our purchases on Amazon*, and reflexively browse our favorite feed-based social products to kill time (Facebook*, TikTok, etc). It’s the offline equivalent of hanging out with friends on the highway median.

On the internet, near zero marginal costs of distribution and powerful network effects make this handful of companies very powerful. If you haven’t read Ben Thompson’s canonical post on Aggregation Theory, now would be a good time to check it out.

If you want to sell a product online, publish a game, or distribute a new app you built, you must pay a tax to one of several dominant aggregators. “Real estate” on the internet can therefore be much more competitive than it is in the physical world, where you pay a market-based rent, but foot traffic comes for free. A few digital companies have been able to grow initially by hacking distribution on someone else’s platform (e.g. Zynga on Facebook, Foursquare on Twitter, Airbnb* on Craigslist), but the bigger platforms eventually stop the fun. Very rarely, inherently viral digital products like Snapchat* or WhatsApp figure out an independent growth model.

This dynamic has begun to change in recent years. With its “arm the rebels” maxim, Shopify* has demonstrated a path for small, online businesses to get on the same footing as Amazon in their own niches. Wix and Squarespace have followed in this direction too. Substack is attempting to do the same in media. Vertically-oriented marketplaces like Outschool* have built platforms for individual creatives to find and engage audiences.

Yet, it’s still quite hard to build an audience online when you (a) don’t have name ID from another platform, (b) aren’t a naturally talented social media promoter, or (c) are creating in a small niche. Even if you are able to build an audience, it’s really hard to monetize it on a big platform unless you’re absolutely massive. For these reasons, Li Jin of Atelier Ventures argued that the creator economy needs a middle class:

The current creator landscape more closely resembles an economy in which wealth is concentrated at the top. On Patreon, only 2% of creators made the federal minimum wage of $1,160 per month in 2017. On Spotify, artists need 3.5 million streams per year to achieve the annual earnings for a full-time minimum-wage worker of $15,080, a fact that drives most musicians to supplement their earnings with touring and merchandise. In contrast, in America in 2016, 52% of adults lived in middle income households, with incomes ranging from $48,500 to $145,500.

A recent post by Cooper Turley and Kinjal Shah advanced my own thinking on this topic. They wrote about online “micro-economies” and what it takes for niche communities to develop an audience and a business model. The vision is that “the shift from Web2 to Web3 [will] create revenue streams which prioritize community ownership over individual ownership.”

Web3 is a new vision of the internet. It takes us away from today’s centralized internet, where data is stored in servers managed by trusted counterparties like Facebook and Google, to a decentralized internet, where a trustless network of peer-to-peer servers manages and verifies data. The network is mediated by various, composable blockchains working together towards a common goal. As Patrick Rivera explains in this presentation, the gravity of the data inside of these trusted counterparties in a traditional client-server architecture leads to monopolistic behavior, centralized control, and a single point of failure for these services.

According to Patrick, Web3 solves these problems by decentralizing governance, pushing data ownership to the individual participants in the network, and establishing a global state. The main challenges to Web3 are technological, but at the rate of change we’re seeing now in blockchain tech, many of those problems will be solved in the near future.

What would solving these problems mean for creators? Most importantly, it would allow fans to invest behind individual creative projects. For example, the aforementioned “Rise of Micro-Economies” post was written on Mirror, a decentralized blogging platform that employs one of the authors. You can see the ownership of the post is split 40%/40% between the two authors, with the remaining 20% split between other contributors — both named and anonymous.

When the scale of investment is proportional to the addressable market of the project, even the smallest creators can bootstrap. Furthermore, their success is financially aligned with the goals of their audience. Equity isn’t just defined in a corporate context; it can be defined on a creator-, or even project-level.

Some readers know that I played music pretty extensively in high school and college. My friends and I would get into bands often before they were widely known. For example, my bandmate Andrew saw John Mayer perform at a local record store (when those existed) in 2001. Mayer’s iconic debut album Room for Squares came out that June. I’m fairly certain that Andrew purchased the album at that event. Imagine if he were able to roll his purchase into tokens tied to the future royalty streams associated with “Your Body is a Wonderland” or “Why Georgia?”. As a fellow musician and fan of acoustic guitar music, Andrew was just as much of an authority on Mayer’s future success as any big label A&R executive.

If the micro-economy vision comes to fruition, college kids hearing their favorite bands play in local coffee shops will be able to participate in those bands’ future success. Doing so will make them even more likely to promote those bands to others — completing a virtuous cycle that funds more artistic production. The same principle could apply to writers, artists, and any manner of creator. The power shift from aggregators to the creators and their fans will be a massive value transfer away from middlemen to those who make things people love, and to those who enjoy them.

I’m excited to participate in this shift as an investor and, most importantly, a fan.

Tweet of the Week

Enjoyed this newsletter?

Getting Drinking from the Firehose in your inbox via Substack is easy. Click below to subscribe:

Have some thoughts? Leave me a comment:

Or share this post on social media to get the word out:

Disclaimer: * indicates a Lightspeed portfolio company, or other company in which I have economic interest. I also have economic interest in AAPL, ABNB, ADBE, ADSK, AMT, AMZN, BABA, BRK, BLK, CCI, COUP, CRM, CRWD, GOOG/GOOGL, FB, HD, LMT, MA, MCD, MELI, MSFT, NFLX, NSRGY, NEE, NET, NFLX, NOW, NVDA, PINS, PYPL, SE, SHOP, SNAP, SPOT, SQ, TMO, TWLO, VEEV, and V.

this isn't terrible; but, a "purely" decentralized future is immature — it'll be heterogenous, which is, by definition, decentralized up and down the entire tech / philosophical stack.

missed it be just a bit.